Credits - Truffle Security

You can access data from deleted forks, deleted repositories and even private repositories on GitHub. And it is available forever. This is known by GitHub, and intentionally designed that way.

This is such an enormous attack vector for all organizations that use GitHub that we’re introducing a new term: Cross Fork Object Reference (CFOR). A CFOR vulnerability occurs when one repository fork can access sensitive data from another fork (including data from private and deleted forks). Similar to an Insecure Direct Object Reference, in CFOR users supply commit hashes to directly access commit data that otherwise would not be visible to them.

Lets Understand via an example

Accessing Deleted Fork Data

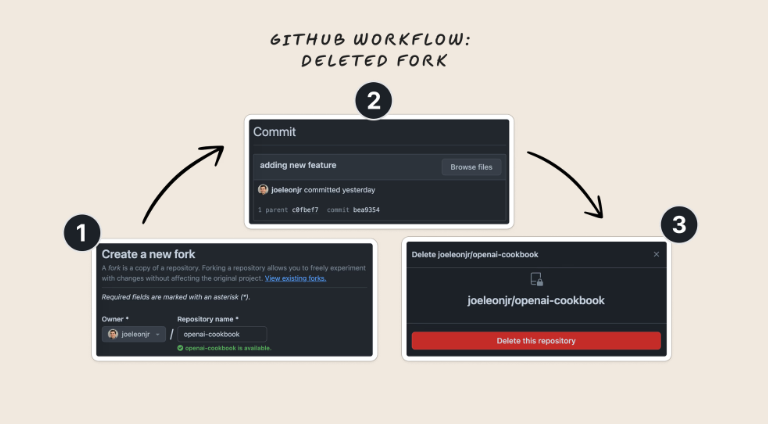

Consider this common workflow on GitHub:

- You fork a public repository

- You commit code to your fork

- You delete your fork

Is the code you committed to the fork still accessible? It shouldn’t be, right? You deleted it.

It is. And it’s accessible forever. Out of your control.

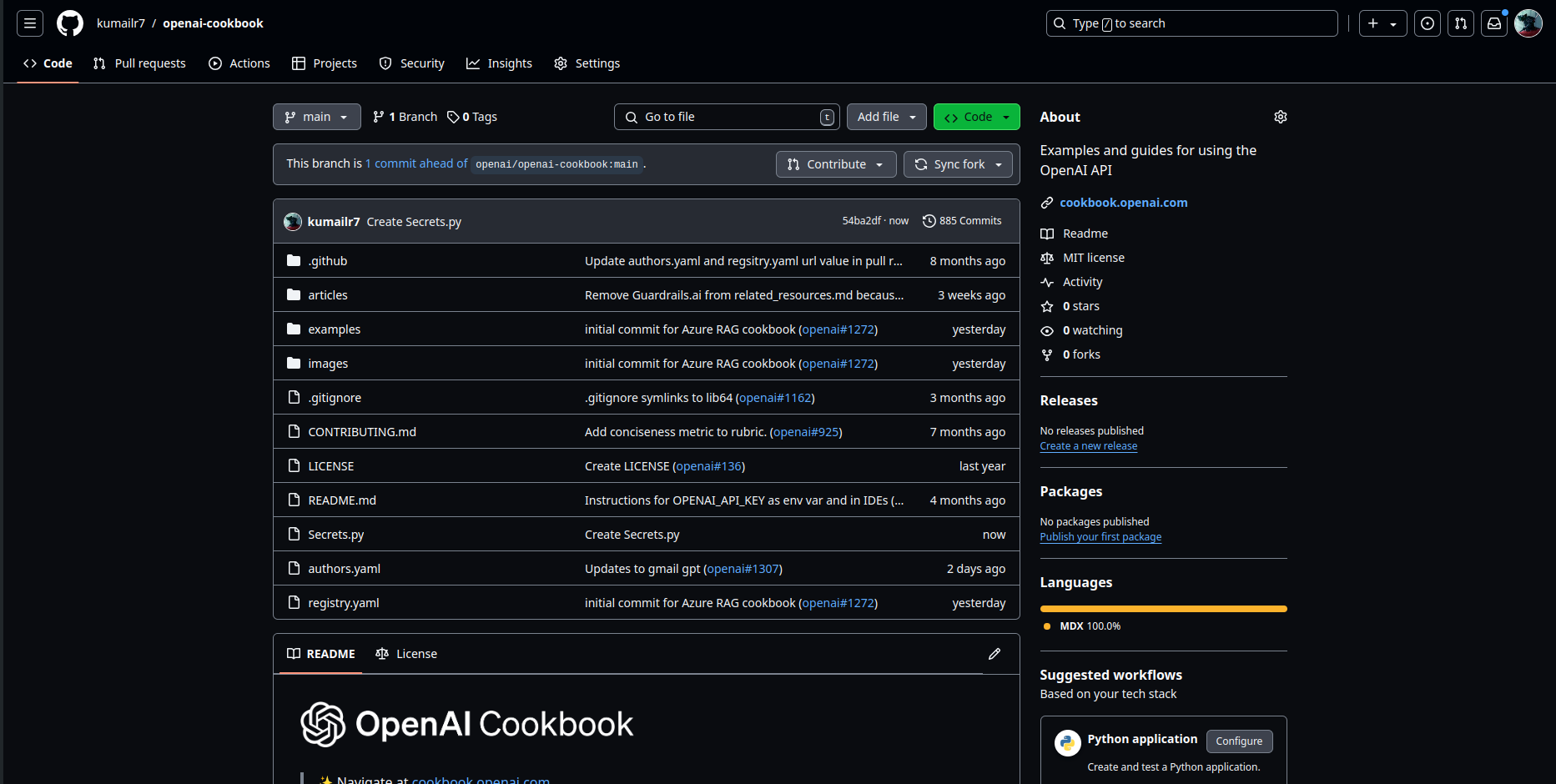

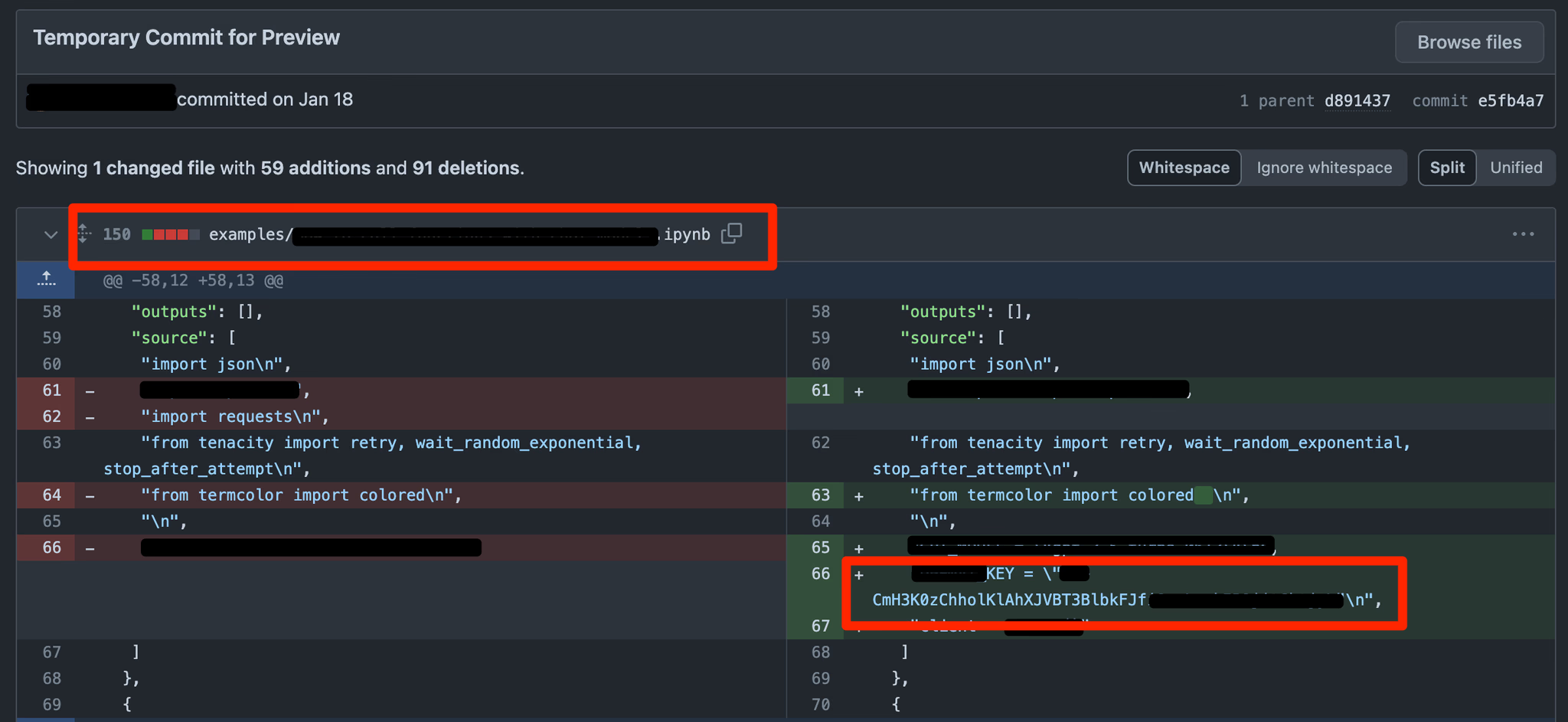

- Here down below you can see that i have fork an Openai-cookbook repo which is Public

- As its forked so its stored on your side , and now lets say you create a feature.py or stored some creds accidentally

NOTE :- This is an example , never store secrets or sensitive data on Repository

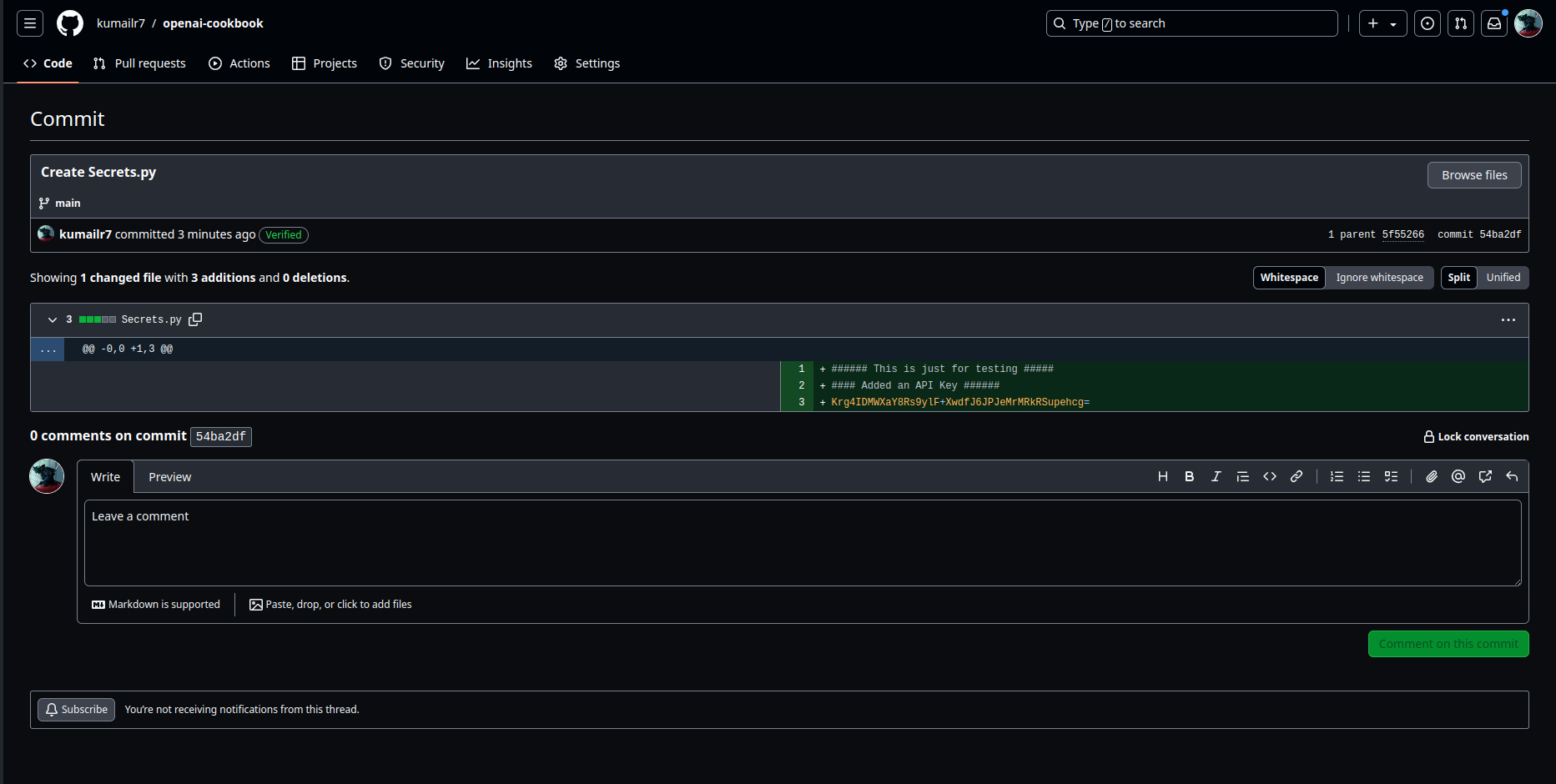

Now you would had deleted the commit / file / forked repo

But the secrets can be accessed easily

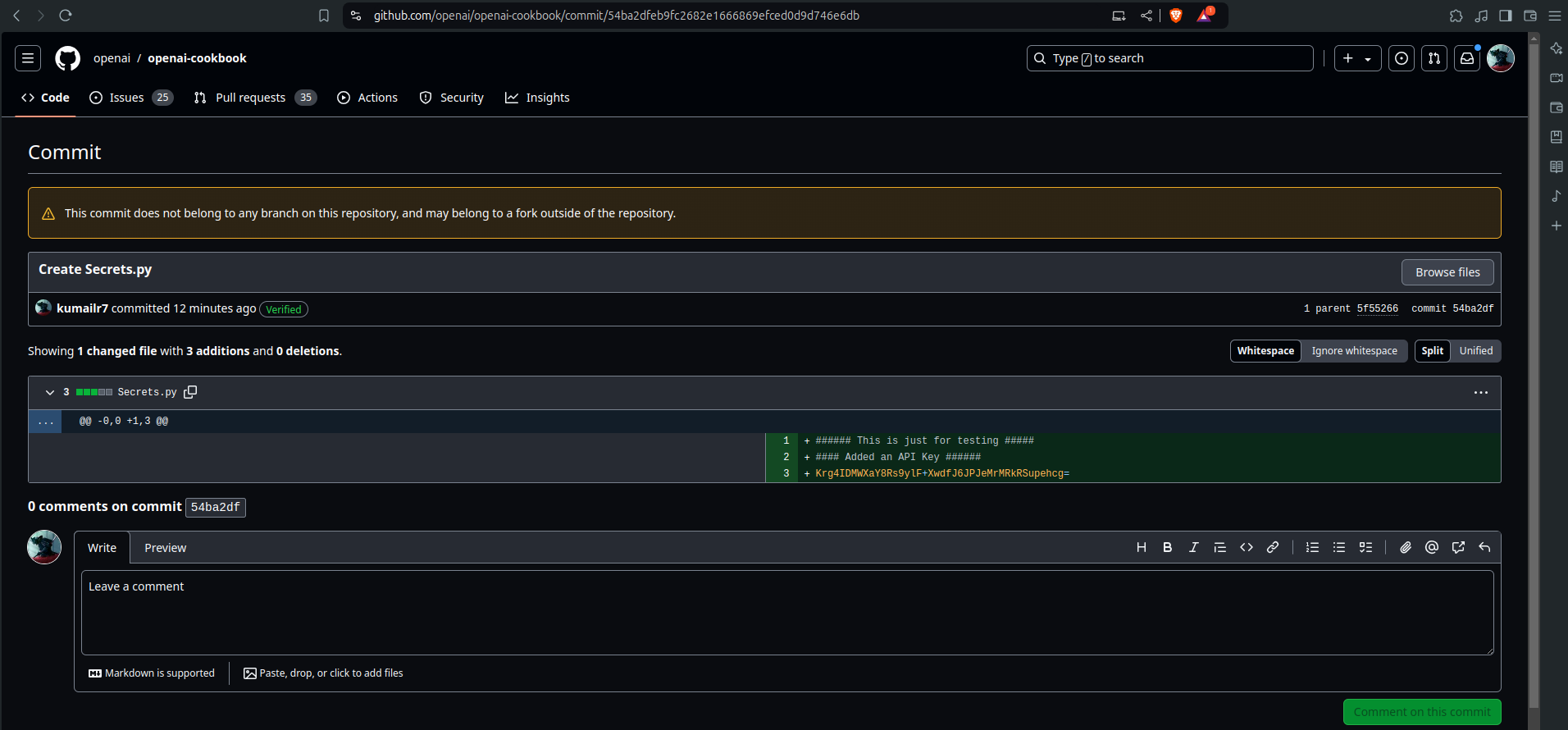

- Here the forked repo has been deleted , everything is gone but the main repo is still there right ?

- So i can retrieve the secret api key by getting the commit SHA of the file and pasting against the main repo and bravo we got it

You might think you’re protected by needing to know the commit hash. You’re not. The hash is discoverable. More on that later.

Now lets understand this Github Bug

How often can Truffle Hog find data from deleted forks?

Pretty often. They surveyed a few (literally 3) commonly-forked public repositories from a large AI company and easily found 40 valid API keys from deleted forks. The user pattern seemed to be this:

-

Fork the repo.

-

Hard-code an API key into an example file.

-

Do Work

-

Delete the fork.

But this gets worse, it works in reverse too:

But this gets worse, it works in reverse too:As we move ahead one question , how any attacker or hacker can get a commit SHA of the delete repo , i mean How ??

How do you actually access the data?

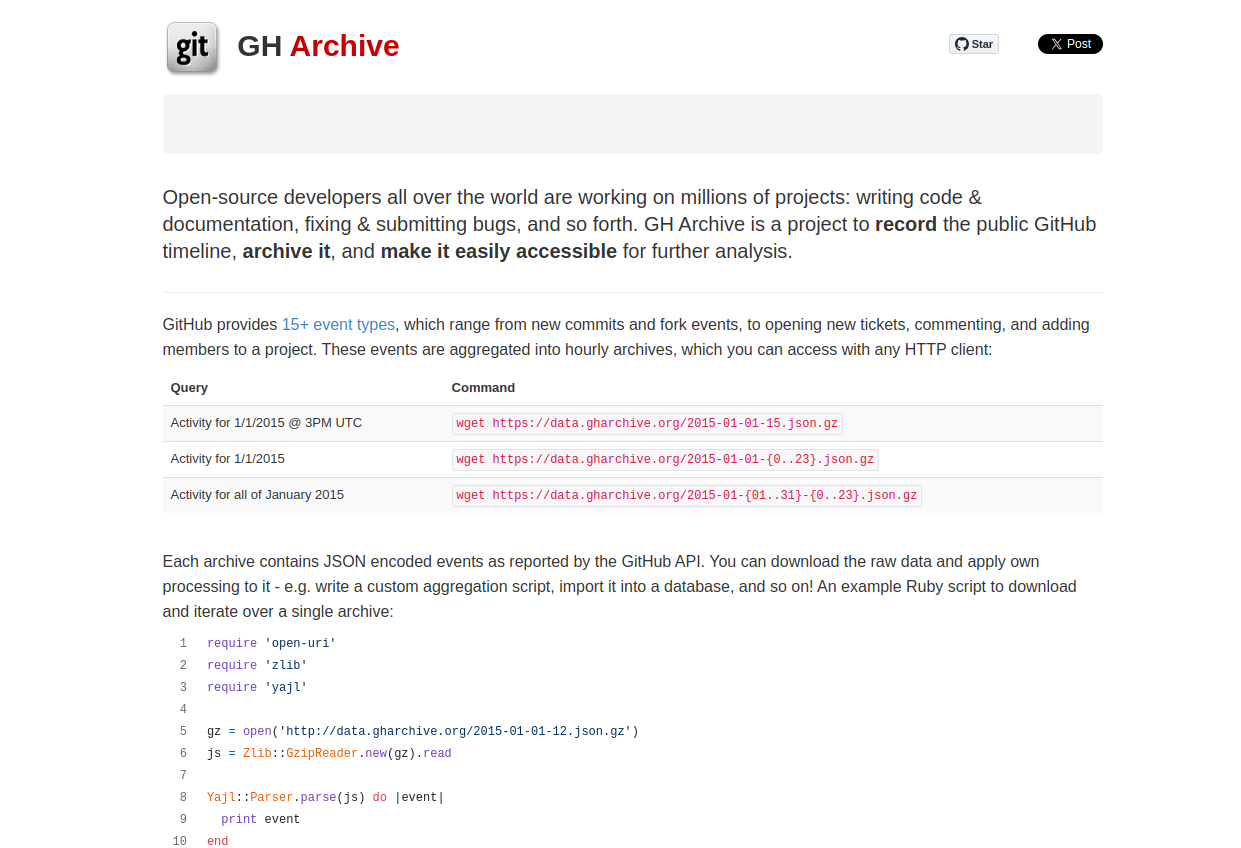

Well , there is a way as well , there is a site know as GH archive where the record of public repos are saved or archived

Here is just an example of an Json Tar file being downloaded [2024-04-27] and extracted , after extracting you can see easily see the information in the json , so the attacker would filter out the json using python script or shell script Note :- Content out the file is Blurred out for Security Reasons

Now the attacker can get the commit SHA of the repo and can do a CFOR

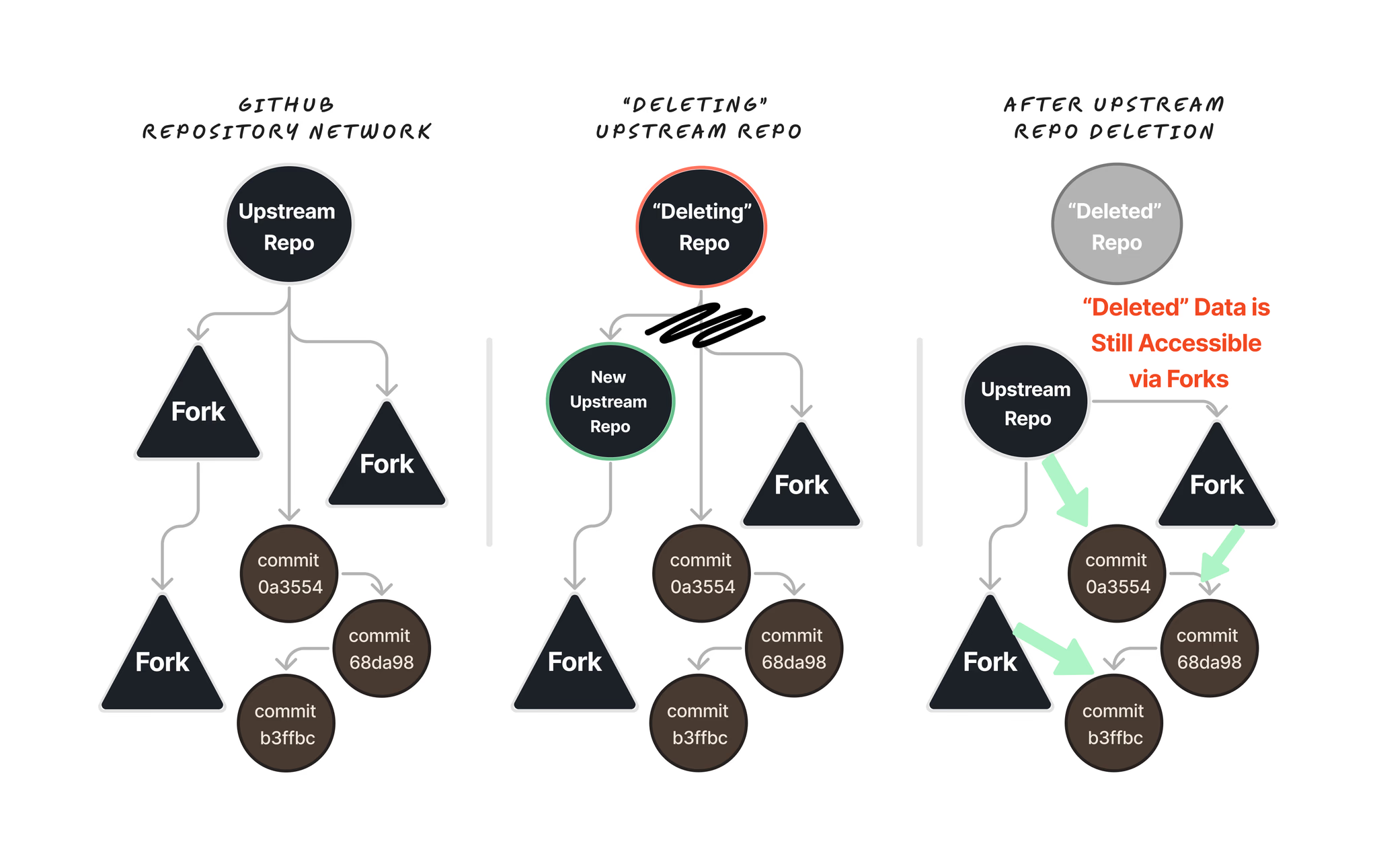

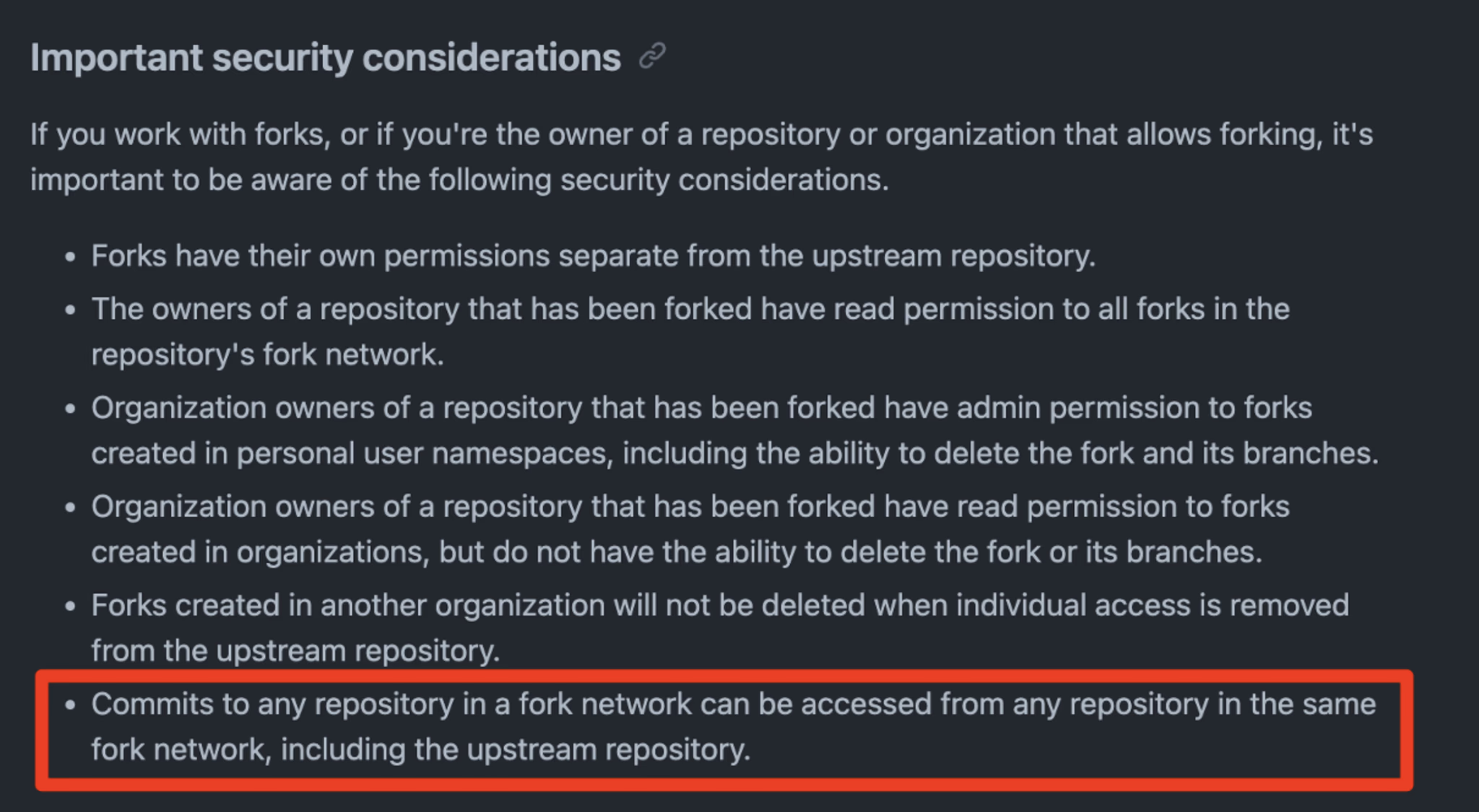

- GitHub stores repositories and forks in a repository network, with the original “upstream” repository acting as the root node. When a public “upstream” repository that has been forked is “deleted”, GitHub reassigns the root node role to one of the downstream forks. However, all of the commits from the “upstream” repository still exist and are accessible via any fork.

This isn’t just some weird edge case scenario. At Truffle Hog this unfolded last week

I submitted a P1 vulnerability to a major tech company showing they accidentally committed a private key for an employee’s GitHub account that had significant access to their entire GitHub organization. They immediately deleted the repository, but since it had been forked, I could still access the commit containing the sensitive data via a fork, despite the fork never syncing with the original “upstream” repository.

The implication here is that any code committed to a public repository may be accessible forever as long as there is at least one fork of that repository.

It gets worse more

But before that , lets get back to basics

What

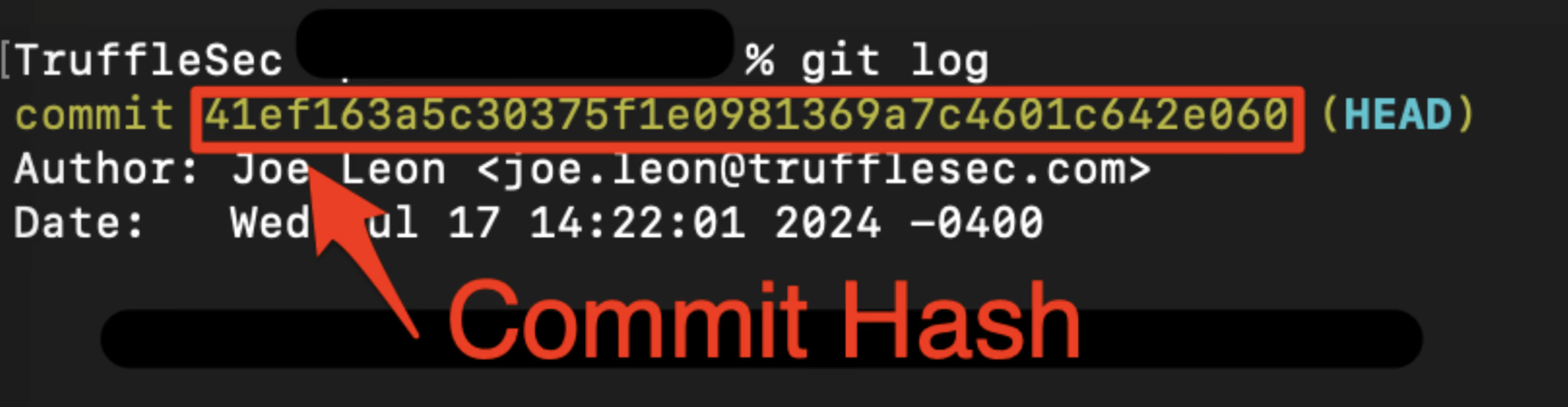

- In Git, each commit is identified by a unique SHA-1 hash, often referred to as the commit SHA or commit hash. This SHA-1 hash is a 40-character hexadecimal string that uniquely identifies the commit and ensures the integrity of the repository. It looks something like this: d6f8d6a0c69a8a5c19a3d8b5f6d8a5c6a8b6d8f6

- Although the full commit SHA is 40 characters long, Git allows you to use a shortened version of the SHA for convenience. Often, the first few characters (typically 4-7) are enough to uniquely identify a commit within a repository. Here’s how you can trace a commit using only the first 4 digits of the SHA:

git log --oneline | grep ^ d6f8

This command lists all commits and filters those that start with d6f8.

the attacker can get this 4 digts by iterate 16 ^ 4 = 65536 , To get the SHA

Lets Understand this by an Example:

- Commit hashes are SHA-1 values.

And All these are managed by GH Archived as shown above

Accessing Private Repo Data

Consider this common workflow for open-sourcing a new tool on GitHub:

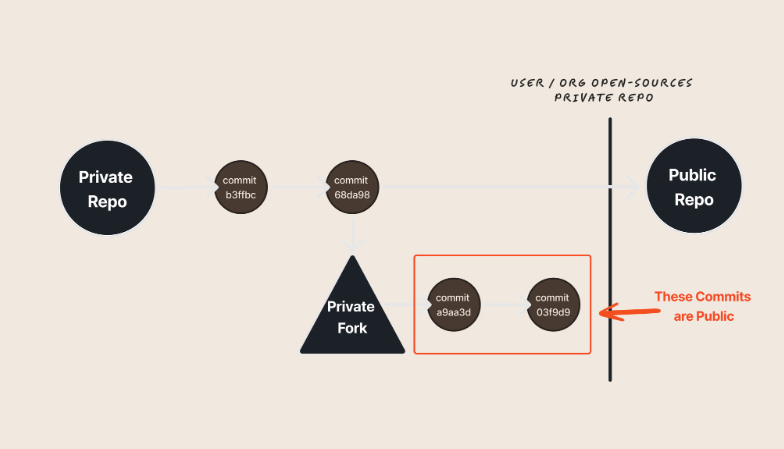

- You create a private repo that will eventually be made public.

- You create a private, internal version of that repo (via forking) and commit additional code for features that you’re not going to make public.

- You make your “upstream” repository public and keep your fork private.

Are your private features and related code (from step 2) viewable by the public?

Yes. Any code committed between the time you created an internal fork of your tool and when you open-sourced the tool, those commits are accessible on the public repository.

Any commits made to your private fork after you make the “upstream” repository public are not viewable. That’s because changing the visibility of a private “upstream” repository results in two repository networks - one for the private version, and one for the public version.

Unfortunately, this workflow is one of the most common approaches users and organizations take to developing open-source software. As a result, it’s possible that confidential data and secrets are inadvertently being exposed on an organization’s public GitHub repositories.

GitHub’s Policies

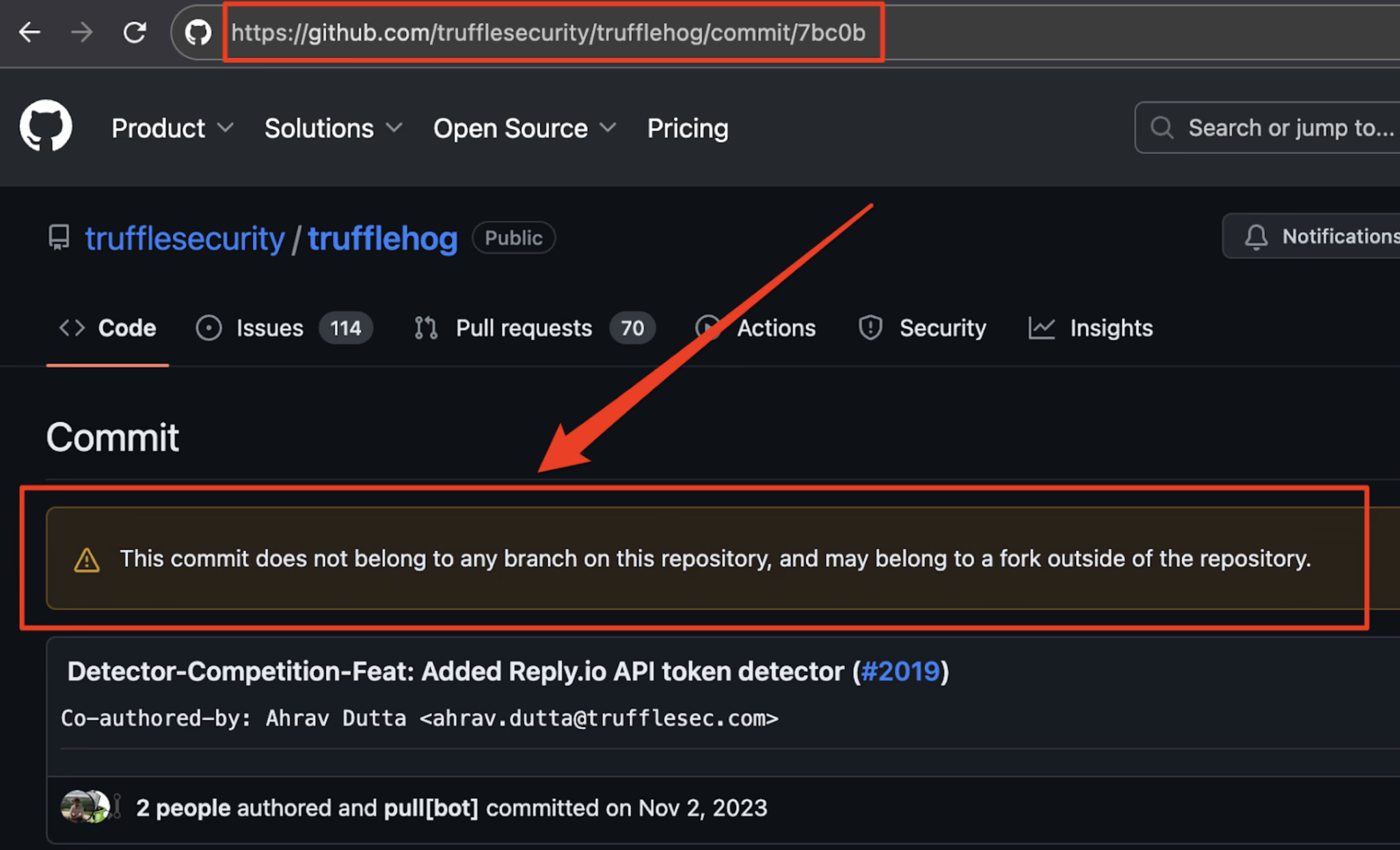

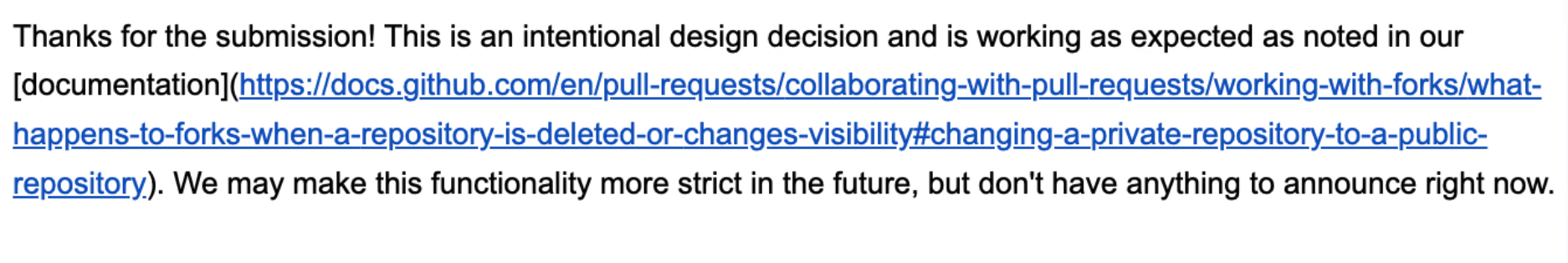

submitted findings to GitHub via their VDP program. This was their response:

After reviewing the documentation, it’s clear as day that GitHub designed repositories to work like this.

Appreciate that GitHub is transparent about their architecture and has taken the time to clearly document what users should expect to happen in the instances documented above.

The main Issue is that:

The average user views the separation of private and public repositories as a security boundary, and understandably believes that any data located in a private repository cannot be accessed by public users. Unfortunately, as we documented above, that is not always true. Whatsmore, the act of deletion implies the destruction of data. As we saw above, deleting a repository or fork does not mean your commit data is actually deleted.

Implications

We have a few takeaways from this:

-

As long as one fork exists, any commit to that repository network (ie: commits on the “upstream” repo or “downstream” forks) will exist forever.

- This further cements our view that the only way to securely remediate a leaked key on a public GitHub repository is through key rotation. We’ve spent a lot of time documenting how to rotate keys for the most popularly leaked secret types - check our work out here: howtorotate.com.

-

GitHub’s repository architecture necessitates these design flaws and unfortunately, the vast majority of GitHub users will never understand how a repository network actually works and will be less secure because of it.

-

As secret scanning evolves, and we can hopefully scan all commits in a repository network, we’ll be alerting on secrets that might not be our own (ie: they might belong to someone who forked a repository). This will require more diligent triaging.

-

Use Gitea and host your private repos that consist of sensitive data or code , so that it would be secure and safe

-

While these three scenarios are shocking, that doesn’t even cover all of the ways GitHub could be storing deleted data from your repositories. Check out our recent post (and related TruffleHog update) about how you also need to scan for secrets in deleted branches.

-

Make use of Secret or Repo Scanning tool like git leaks or Truffle Security scanner

Finally, while their research focused on GitHub, it’s important to note that some of these issues exist on other version control system products.